Communication from our Aware & Healed Self

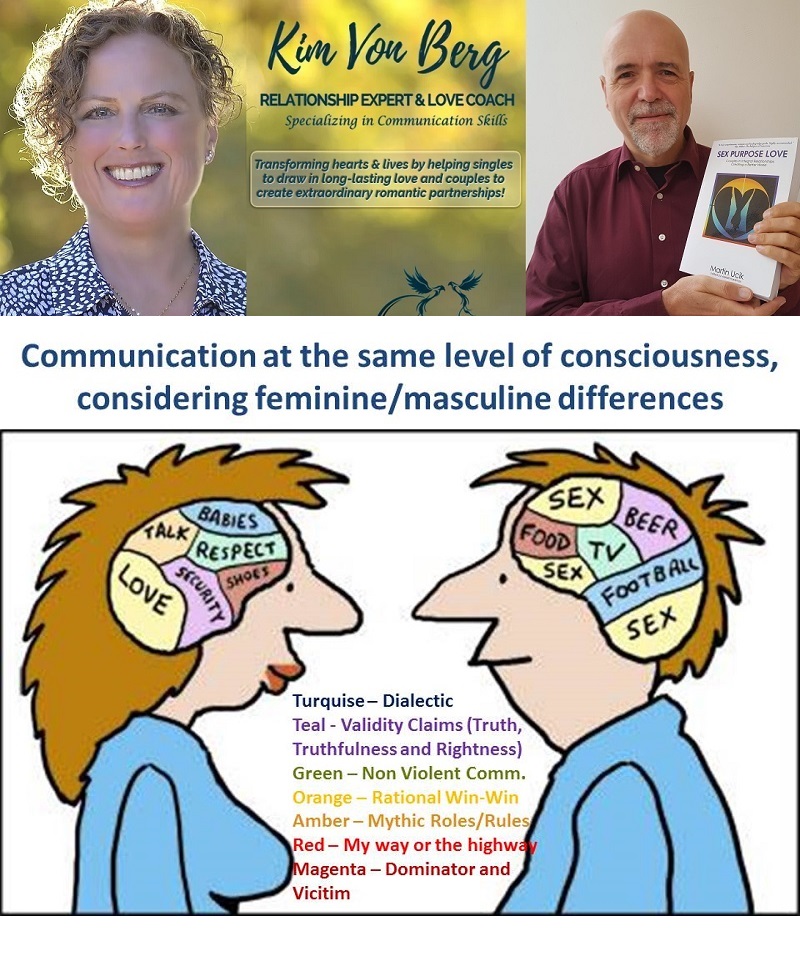

As we see in the image above, men and women at different levels of consciousness use different ways of communicating to find consensus or agreement (encapsulated in the wonderful German word Verständigung, which means to understand and to agree) by giving good reasons for their point of view, experience and intentions that lead to action.

As we see in the image above, men and women at different levels of consciousness use different ways of communicating to find consensus or agreement (encapsulated in the wonderful German word Verständigung, which means to understand and to agree) by giving good reasons for their point of view, experience and intentions that lead to action.

Kim will share with us how she works with her clients on increasing self-awareness and healing of wounds that they can reach “Verständigung” with their partner.

Read more about her work at https://goo.gl/jgFE72 and https://goo.gl/p4yaUr

An Integrated Approach to Male-Female Communication:

Below is an excerpt from Sex Purpose Love about reaching Verständigung that integrates feminine and masculine validity claims in the public and private spheres to coordinate action (Handeln), which Habermas calls “Communicative Action”.

To co-create with an equal and opposite partner with the same rights and responsibilities who shares our Transcendental Purpose, we need to refine the ways we communicate and coordinate our actions in the public and private sphere.

According to Habermas, who takes a pragmatic approach to social philosophy, the meaning of descriptive, propositional (truth) and performative sentences (which not only describe an experienced reality or situation but which also change the social reality they are describing) can be best understood by looking at what words do, and not only at what they say. He maintains that whenever people use language to coordinate their actions, they enter into certain commitments to justify their actions. To him, the function of speech is to create a shared understanding and to establish intersubjective consensus between the speaker and the listener. This is accomplished through giving good reasons, or making what he calls “validity claims,”[i] in three crucial areas:[ii]

- That what is said is objectively true—that there are good reasons for its being believed by the listener, or that he or she can be convinced based on these reasons.

- That what is said is subjectively truthful, which means that the speaker is authentic and sincere about his or her interior experience, such as feelings, moods, desires, beliefs and the like.

- That what is said is morally right and ethically justifiable.[iii]

Unlike the first and last validity claim, the second claim, namely to truthfulness, cannot be assessed through discourse, but only through a comparison of the speaker’s words with his or her behavior/actions. For example, if a man claims to care deeply about his wife, but does not pay much attention to her needs, or if a woman says she unconditionally loves or trusts a man, but constantly nags him to change and emasculates him, we would have grounds for doubting the sincerity/validity of their claims, even if their claims are a matter of self-deception rather than deliberate lying.

In other words, his theory of communicative action and discourse ethics requires us to bring our words into alignment with our actions through awareness and will. Habermas differentiates between success-oriented arguments and behavior in which the more powerful wins, versus consensus-oriented action—or communicative action—where couples or groups only proceed to physical action after consensus is reached through ethical discourse. In doing so, Habermas transforms the traditional philosophy of the independent subject into a philosophy of communicative rationality. This leads him to propose ethics in which “only those action-norms are valid to which all possible affected persons in the present and future could agree to as participants in rational discourse.”[iv]

Finlayson writes, “The essential point of Habermas’ theory is that discourse can fulfill its social and pragmatic function all the better because it is a dialogical process, a process that draws people together into meaningful argument. The process of justifying a norm always involves more than one person, since it is a question of one person making the norm acceptable to another.”[v]

There are several additions to Habermas’ model of communicative action that are important for love relationships.

The German philosophical anthropologist Prof. Ferdinand Fellmann (Author of The Couple) maintains that where isolated individuals meet we get at best communities of purpose or partnerships of convenience which lack the foundational element of the intersubjective and inter-objective commonality of couples [at the level of all seven chakras]. He states that communication between couples has its own rationality that is different from the pragmatic theory of linguistic meaning, and that Habermas skips this anthropological stage and stays in the realm of communicative rationality. Habermas speaks of rational crisis, legitimacy crisis, motivational crisis, but not of communicative crisis, as the state of modern marriages proves that there is always potential for conflict in inter-subjectivity and inter-objectivity. This is because Upper Left interior intention and Upper Right exterior behavior as well as Lower Left cultural values and Lower Right social realities are often misaligned.

Similarly, in 1932, Karl Jaspers differentiated communication into “Daseinskommunikation” (inter-objective “being communication” located in the right quadrants) and “existenzielle Kommunikation” (intersubjective “existential communication” located in the left quadrants.) He noted that there are risks in opening up to interior existential communication as our exterior behavior is often not aligned with our interior values. “In public and even intimate groups we can fake it, but not in intimate relationships, which makes them so challenging,” he wrote. As early as 1948, he argued for “an integral reasoning in which the objective and subjective sides don’t fall apart.”[vi]

Again Fellmann: ”Since love relationships are anchored in Eros, the driving force [co-creative impulse] which pervades all areas of life from friendships to economy, couples are different from other forms of social coherence-building instruments such as language, shared myths, or values as the binding element between individuals and society, because couples share an a-priori or pre-verbal direct/immediate experience of each other when freed from cultural conditioning.”[vii]

And lastly, Tugendhat critiques Habermas because the latter’s orientation towards reason (validity claims) does not touch upon intersubjective feelings and emotions (affects).

Tugendhat explains in his Lectures on Ethics (Vorlesungen über Ethik) that Habermas’s concept of communication is insufficient due to the fact that its strong orientation to reason does not touch on the emotional side of interpersonality. He said, “According to Habermas, ‘understanding’ is essential for communicative action. But this is only a mutual understanding about the interests of those involved, whereas communication […] is with the other, and this is a kind of communication that is only possible with the affects of the other. [Not only] interests are agreed upon but the affects as well. The aim is not [only] a balance of interests but a harmony of affects.”[viii]

Co-creation in Integral Relationships requires us to integrate both forms of communication: Habermas’s masculine theory of communicative action and the feminine form of compassionate or Non-Violent communication[ix] where the expression of feelings, needs and request are used to create an authentic emotional connection. Both are absolutely vital, because the latter often doesn’t lead to exterior action after communication took place, while the former does not consider the underlying affects that guide much of our reasoning and behavior.

For example, truthfully communicating interior loving feelings, needs for closeness, and romantic desires do not necessarily lead to exterior action of staying in a love relationship when there are challenges that would require healing and growth, while at the same time, exterior action after rational and moral reasoning alone why a couple should be together does not create the necessary harmony of affects for a relationship to thrive.

This integration is accomplished in love relationships where equal and opposite partners with the same rights and responsibilities in the public and private sphere apply discourse ethics that make masculine and feminine validity claims and leads to action in both spheres after mutual understanding and agreement is reached.

Integrated Compassionate Rational Communicative Action Model

This expanded communicative action is shown below.

| Female sexual Selection for: | |||||||||||

| Empathy | Intelligence | Creativity | Kinesthetic | ||||||||

| Leads to more: | |||||||||||

| Goodness | Truth | Beauty | Functioning | ||||||||

| Validity Claims to what is: | |||||||||||

| Morally/Ethically Right | Objectively True | Truthful | Practical | ||||||||

| Feminine / Private Sphere | Masculine / Public Sphere | ||||||||||

| Care | Compassion | Feelings | Relationships | Rights | Justice | Rationality | Autonomy | ||||

| Balanced and Harmonized along the Seven chakras in Both Spheres | |||||||||||

The model starts out at the top with the sexual selection process of females choosing males who show empathy, intelligence, creativity, and kinesthetic abilities as mates for co-creation and procreation and share their Transcendental Purpose.

The second row shows that choosing good matches in these areas leads to more goodness, truth, beauty, and functioning that enhance survival rates and quality of life.

Goodness is defined as what is morally right and ethically good and considers all affected parties, including future generations.

Truth is defined as what consistently and un-problematically holds true in the daily practical engagement with reality or accurately represents actual states of affairs, or, if problems arise, is based in critical testing as seen in scientific inquiry, which combines empirical arguments with practical actions such as field studies and laboratory experimentation.[x]

Beauty is defined by what gives pleasure to the senses or pleasurably exalts the mind or spirit, and what brings happiness and creates cultural cohesion.

Functioning is defined by what works or operates in a proper way and is sustainable.

In the third row, we see the validity claims to what is morally right and ethical, objectively true, subjectively truthful, and practical.

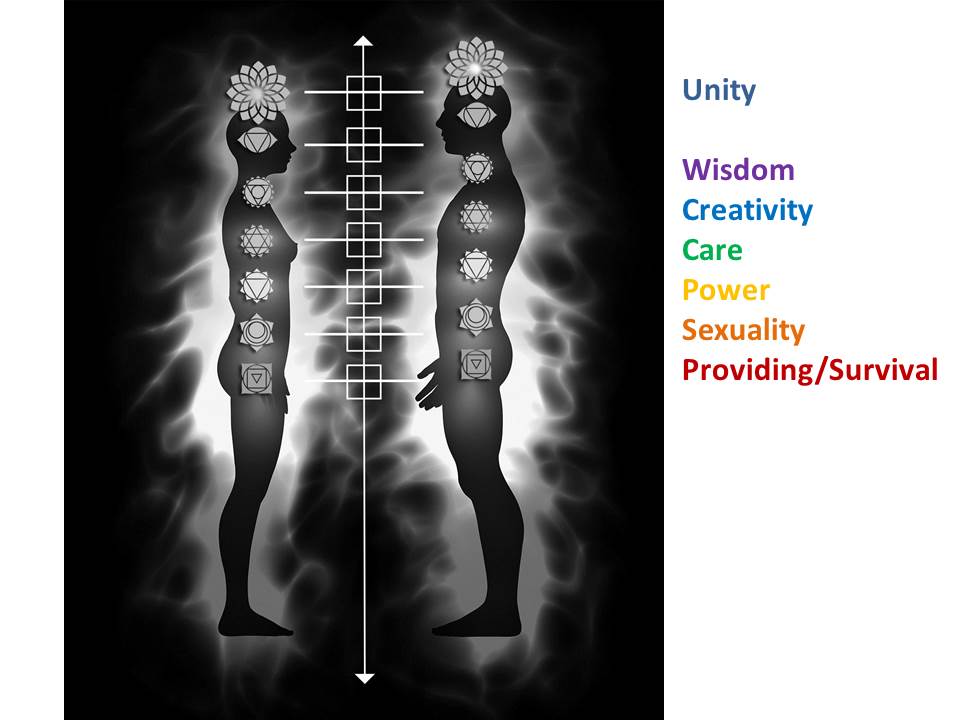

The fourth row shows that traditionally, females made feminine validity claims of care, compassion, feelings, and relationships, typically at the level of the 2nd, 4th and 6th chakra in the private sphere, and males made masculine claims of rights, justice, rationality, and autonomy, typically at the level of the 1st, 3rd, and 5th chakra in the public sphere.

Integral couples co-create by each of them making feminine and masculine validity claims to what is right, true, truthful, and practical in the public and private sphere at the level of all seven chakras, as indicated by the four quadrants as shown below.

As proposed by Habermas, Integral couples consider the interests of all affected parties—including the unborn—and only proceed with action once “Verständigung” between them is reached.

What is good, true, beautiful and functional in the public and private sphere at the level of each chakra is neither decided by an independent subject that stands over and against a plurality of other thinking and acting subjects and the world, as suggested by modernism, postmodernism, or the “philosophy of consciousness,” nor by systems created by higher authorities in science, philosophy, art, religion, or government that reached a critical mass of consensus to impose it on others, as is usually the case in mythic societies. Instead, what is good, true, beautiful, and functional is defined by the co-creation between couples who balance and harmonize healthy feminine and masculine polarities between their four quadrants at the level of all seven chakras in life-long relationships. Once the couple has reached consensus in this way, it can enter into the same form of communicative action with others, and becomes the foundation for functional families, thriving communities, flourishing societies, and peaceful nations.

This requires that we become fully human through being seen, met, and inspired to align our values with our behavior and to continue to learn, heal grow and awaken at the level of all seven chakras, which is only possible in committed intimate love relationships. This is true for both heterosexual and same-sex couples.

The beauty of the Integral love relationship model is that it does not immediately require a critical mass of 10% of the population to create the trickle-down effect to earlier levels, as it not only attempts to pull people up from Green and Teal to Turquoise, but also reaches down to meet people at earlier levels and to support them in identifying their Transcendental Purpose which they can then share with an equal and opposite partner at their particular level to co-create more goodness, truth, beauty, and functioning while living their Biological Purpose, including procreation, in a healthy sustainable love relationship.

If we don’t succeed in making these shifts and following this new vision for our love relationships, we may be one of the next endangered species or, at the very least, experience tremendous hardship through personal loneliness, environmental destruction, social upheaval, spreading terrorism, increasing corruption, and global wars for centuries or millennia to come.

Endnotes:

[i] From the German word “Geltung” or “Gültigkeit,” forming a close relationship between reason and consensus.

[ii] For a more complete outline of Habermas’s “Pragmatic Meaning Programme” see page 28 – 46 in Habermas: A Very Short Introduction.

[iii] From Habermas: A Very Short Introduction page 92-95:

What is ethical discourse?

The term ‘ethics’, as Habermas often notes, has both an ancient and a modern use. It stems from the ancient Greek word ethos, which referred both to the customs of a polis, or city-state, and to the habits and character of its people or citizens. In modern times, Hegel uses the term Sittlichkeit (commonly translated as ‘ethical life’) to denote the concrete way of life of a community, replete with its values, ideals, and self-understandings, on the one hand, and practices, institutions, and laws, on the other.

Habermas’s conception of ethical discourse has several distinguishing features.

- Ethical discourse is ‘teleological’ in the senses that it concerns ‘the choice of ends’ and the ‘rational assessment of goals’. Where pragmatic discourse takes one’s desired ends as given, and deliberates the best means to achieve them, ethical discourse evaluates those ends.

- Ethical discourse evaluates ends by assessing what is ‘good for me’ or ‘for us’. These are particular, not universal, goods. (Morality, by contrast, deals with questions of right and wrong, which insofar as they are good (or bad) are supposed to be universally good (or bad), since they affect everyone in the same way.) The notion of the good that ethical discourse puts in play relates both to the individual life history of the person and to the collective life of the community. Habermas calls discourses concerning an individual life ‘ethical-existential’, and those concerning the collective or group ‘ethical-political’.

- Ethical discourse is prudential: it concerns the ways in which we organize the satisfaction of our desires and ends with a view not just to present but also to future happiness and to our happiness all things considered.

- Ethical discourse makes salient the values that are germane to an individual’s life history and to the particular tradition or cultural group to which that individual belongs. Habermas has a very specific concept of a value. A value is a basic symbolic constituent of culture or ethical life. To say that values are basic means that they cannot be analyzed into anything more simple, and explained in a more primitive vocabulary, say, of preferences, desires, needs, or reasons. Values determine preferences, not vice versa. They help shape our needs, desires, and interests, which, Habermas argues, are not given to us fully formed by our biology or social heritage, but always stand in need of interpretation. Because values are tightly bound to the fabric of a particular community, each individual in the course of her socialization into the institutions and practices of that community will absorb and internalize its basic values. Hence these values will come to form a core component of the individual’s self-identity. Values are thus not ‘out there’ like natural facts, existing independently of us. They are engrained in us and we are in the midst of them. Consequently, although individual values are susceptible to interpretation and to gradual change, they are not something from which human beings can very easily detach or abstract themselves. Finally, values are by their nature gradual, whilst norms are absolute: values admit of higher and lower degrees, whereas norms are either valid or not. While it makes little sense to say that one action is more morally wrong than another, it makes perfect sense to say that one choice is better than another.

- Habermas’s understanding of the concepts of good and of value bear upon a logical feature of ethical discourse. The advice, judgements, and orders of preference in which ethical discourses issue, have only ‘relative’ or ‘conditional’ validity. (By contrast, the norms in which successful moral discourses issue are universally and unconditionally valid. Whereas a valid moral norm is meant to hold across different and competing cultural traditions, values only hold within a particular tradition or cultural group.)

- Ethical discourse concerns the self-understanding of the individual or group. Whether about an individual or group, ethical questions are broadly speaking hermeneutic questions. They aim at self-clarification, self-discovery, and to an extent also self-constitution. When successful, they issue in judgements or advice about which ends, values, or interests to pursue for the sake of one’s overall good.”

- Ethical discourse makes a validity claim to authenticity (DEA, 41). It is not very clear how this validity claim fits in with the other three validity dimensions of truth, rightness, and truthfulness. Authenticity appears to be an analogue of truthfulness in the practical domain. It does not fit in with Habermas’s neat triadic schema because, by the time he introduces this revision to discourse ethics, he is not so concerned to make it backwards compatible with his pragmatic theory of meaning. This lack of fit indicates that our moral conceptions are much messier than Habermas’s neat conceptual distinctions make them look”

| Synopsis of the difference between ethical and moral discourse | ||

| Ethics | Morality | |

| Basic concept | Good/bad | right/wrong just/unjust |

| Basic unit | Values | Norms |

| Basic question | What is good for me or us | What is just? What ought I to do and why? What is right? |

| Validity | Relative and conditional | Absolute and unconditional |

| Type of theory | Prudential, teleological | Deontological* (duty, obligation or rule) |

| Aims | Advice, judgment preference ranking | Established, valid norms; discovering duties |

* Deontology is the study of that which is an “obligation or duty,” and consequent moral judgment on the actor on whether he or she has complied. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deontological_ethics

[iv] Habermas: A Very Short Introduction page 79.

[v] Ibid page 79

[vi] The Couple, page 86

[vii] Ibid 48

[viii] Ibid page 92-93

[ix] See endnote 1188 about Non-Violent Communication

[x] Habermas proposes a “pragmatic epistemological realism.” His theory of truth is realist in holding that the objective world, rather than ideal consensus, is the truth-maker. If a proposition (or sentence, statement) for which we claim truth is indeed true, it is so because it accurately refers to existing objects, or accurately represents actual states of affairs—albeit objects and states of affairs about which we can state facts only under descriptions that depend on our linguistic resources. The inescapability of language dictates the pragmatic epistemological character of his realism. Specifically, Habermas eschews the attempt to explicate the relationship between proposition and world metaphysically (e.g., as in correspondence theories). Rather, he explicates the meaning of accurate representation pragmatically, in terms of its implications for everyday practice and discourse. Insofar as we take propositional contents as unproblematically true in our daily practical engagement with reality, we act confidently on the basis of well-corroborated beliefs about objects in the world. What Habermas calls “theoretico-empirical” or “theoretical” discourse becomes necessary when beliefs lose their unproblematic status as the result of practical difficulties, or when novel circumstances pose questions about the natural world. Such cases call for an empirical inquiry in which truth claims about the world are submitted to critical testing. Although Habermas tends to sharply separate action and discourse, it seems more plausible to regard such critical testing as combining discourse with experimental actions—as we see in scientific inquiry, which combines empirical arguments with practical actions, that is, field studies and laboratory experimentation. From https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/habermas/